Welcome to the latest edition of the CONSORTIUM CHARTERED PHYSIOTHERAPISTS blog. Thank you for reading part 1 of ‘managing load to avoid injury’... If you have not read it yet and want to reduce your risk of injury then please click here to do so!

This article has been written by myself (Chris John) and another fellow Physiotherapist and friend Rob Parkinson. Rob is highly skilled physio and works in elite rugby alongside running his own private practice in Gloucester called Pro Performance. You can follow us both on twitter @chrisjohnphysio and @properformrehab

After reading the first blog you will have summarised a few points:

- The optimal amount of load is best for getting fit and trying to avoid risk of injury. Overloading or under loading can result in an increased risk of injury (Dye, 2005).

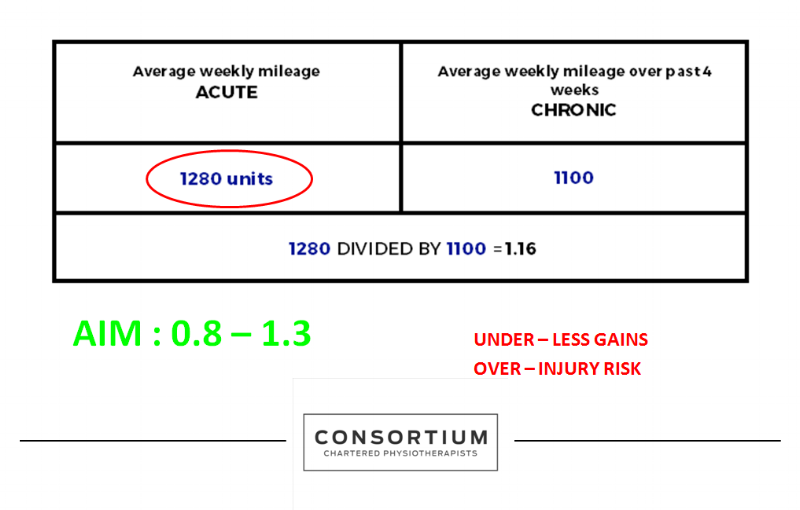

- The acute to chronic workload load ratio is a useful method to monitor your training and ensure you are not over or under loading. The ideal ratio is 0.8 to 1.3 (Gabbett et al, 2016).

Calculating your acute:chronic ratio will help prepare you for competition, improve your performance and should decrease your risk of injury.

My previous blog explains how to use this in a very simple way and is relatively easy to remember. However, the disadvantages to using a simple version like this is that everybody is different. Some of us are tolerant enough to be able to drastically increase our training and not end up getting injured. Some will find the opposite and only need to make small changes and often end up with problems. Some amount of this you cannot control, it will just depend on how you were put together and is simply the way you are. However... there are other factors that will influence how quickly you can progress. Things like your past medical history, age, weight and previous training levels will all have some influence. Using the simple acute to chronic workload ratio that we previously described in part one unfortunately does not account for any of these factors. The other downsides of keeping to a very simplistic model is that it is also very objective as it focuses purely on distance or volume of training and doesn't take into account how hard you went.

For this reason I present to you a more advanced way of calculating your training progression and I will go on to explain this below.

THE ADVANCED VERSION

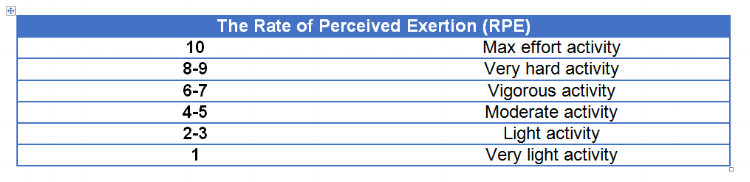

Uses Rate of Perceived Exertion (RPE) (ie 0 no effort, 10 maximum effort)

Calculate your time spent training into units ie. (RPE x number of minutes you undertook that activity for)

You then CALCULATE THE TOTAL FOR THE ENTIRE WEEK

So what is a rating scale?

The ‘Rate of Perceived Exertion’ is a well-known tool in the world of professional sport that is used to measure how the athlete perceives the intensity of workload given (Brito et al, 2016).

THIS CAN BE a game, running, cycling, training, strength and conditioning session, gym session and so on…

The Table below shows the Rate of Perceived Exertion scale.

So how do you work out your acute:chronic ratio using RPE?

You multiple your RPE by the training session time in minutes

(RPE x training session time = units)

EXAMPLE: A 30 minute gym session was an intensity of 7/10 (30 x 7 = 210 units)

You then use this to work out your total units for the acute and chronic weeks

ACUTE LOAD DEFINITION: The sum of load over 7 days

CHRONIC LOAD DEFINITION: The average acute load over the previous 4 weeks (or however many week you chose)

The following example demonstrates how you would calculate the total volume of units for one week of training

you then use this to work out your figure to see if you are in the safe zone or whether you are at risk as demonstrated below

SO LETS RECAP THE BENEFITS OF USING THE ADVANCED VERSION

- It takes into account internal and external factors as YOU score how YOU feel after that specific session (Coutts et al, 2004).

- How YOU progress is then specific to you only (Abbiss et al, 2015). For example, using a prescribed marathon website training program will provide you only with a generic protocol. It is not designed exactly for YOU and does not take into account any of the factors that will affect how quickly you can progress in comparison to someone else.

- You are in then in total control of your own programme; progressing yourself in a SMARTER way, trying to ensure you always work in your ‘sweet spot.' This will leave you better prepared for competition and less likely to get injured (Gabbett, 2016).

So remember, train hard…but train smart!

Thank you for reading.